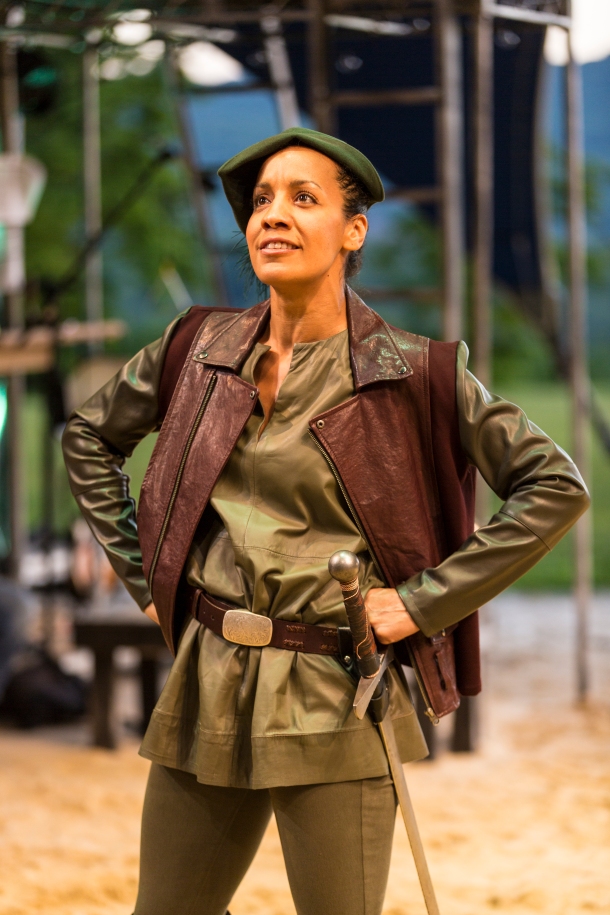

Robyn Kerr as Marion in The Heart Of Robin Hood Hudson Valley Shakespeare Festival Directed by Suzanne Agins. Lighting Design: Jiyoun Chang Costume Design: Sara Jean Tosetti Set Design: Sandra Goldmark Photograph © T Charles Erickson

The first known appearance of the story of Robin Hood with most of its familiar elements (stealing from the rich and giving to the poor; Sherwood Forest; evil sheriff; band of Merry Men) can be found in a mid-fifteenth-century English ballad. The origins of the myth itself date back to the 1300s. The tale transcends medium, springing from medieval ballads to the theater (beginning in the late 1500s) to nineteenth-century children’s tales to novels to film and television. There are currently seven Robin Hood film adaptations in development (ranging from gritty to grittier to futuristic and dystopian), with the first due to come out this fall. So what makes this story resonate across the generations–and especially, why tell it, over and over, right now?

Trying in part to answer that question, The Heart of Robin Hood (a 2011 adaptation by British playwright David Farr), this summer’s family-friendly offering at the Hudson Valley Shakespeare Festival, sets its sights on issues of gender and female autonomy. Its protagonist and moral center is not the “noble outlaw” himself, but Marion, Robin Hood’s love interest. Maid Marian, as she is usually called—Farr uses the variant Marion—enters the story in roughly the early sixteenth century, and from her first appearances, she falls into the category of “strong female character,” rather than, say, “damsel in distress” or “innocent ingenue.” Still, the core of the story generally belongs to its titular character, though the director of The Heart of Robin Hood, Suzanne Agins, notes that Marian is more likely to be the protagonist in the historical novels based on this story than in other genres.

The company of The Heart Of Robin Hood Hudson Valley Shakespeare Festival Photograph © T Charles Erickson

Agins believes that the story’s very malleability keeps it relevant, and that rooting for an underdog is always appealing, even if different eras have vastly different takes on who qualifies as a worthy underdog. “Anyone can tell a version of Robin Hood to support their agenda,” she says. During the McCarthy era in the United States, for example, the Indiana state school textbook commission called for bans of Robin Hood as a communist story. The Heart of Robin Hood makes Marion, more than Robin, the underdog whose journey and growth drive the narrative. The piece becomes a classic coming-of-age story for Marion, though also a journey toward full emotional adulthood for Robin. Agins says, “This tension that’s baked into the play is that although this adaptation posits Marian as the protagonist, it’s really hard when the guy called Robin Hood keeps sneaking into all the scenes.”

Trace Pope as Much Miller in The Heart Of Robin Hood Hudson Valley Shakespeare Festival Photograph © T Charles Erickson

Robin Hood is already a successful outlaw at the beginning of the piece, and he’s not doing nearly so much redistribution of that wealth as you might expect. He lives a life of danger and instability, but it’s a life he’s chosen and will defend to the death. Marion, despite her privilege as the daughter of a wealthy duke, is backed into a corner familiar to women of her era: she doesn’t get to choose the path of her life. Her only option for adulthood is to marry, and marry a man suitable to her station rather than one she may love.

Marion’s sister, Alice, on the other hand, is perfectly content with her lot as a rich man’s daughter destined to marry another rich man’s son. Alice is the only other adult woman in the piece, and her vapid self-centeredness and vanity underline the extent to which Marion’s best qualities–her strength of character, her desire for self-determination, her interest in events outside her castle–put her drastically at odds with the society she lives in. The most independence she can hope for is to turn down an individual suitor or two, or perhaps to successfully delay her marriage until her father returns home from the Crusades. But when Prince John, the ruling regent (while King Richard the Lionhearted is off leading said Crusades), sets his eye on her, refusing isn’t really an option. Prince John is generally a villain in the larger Robin Hood myth; this Prince John raises the stakes by being not just a scheming, venial usurper but also a man of “legendary sexual appetites” who relishes the chance to break a woman’s spirit.

Tora Alexander in The Heart Of Robin Hood Hudson Valley Shakespeare Festival Photograph © T Charles Erickson

Faced with the prospect of marrying John, Marion’s only hope, she thinks, is to run away to the forest and join Robin Hood’s band. Little does she know that women are not allowed in this club, either, and her attempts to bribe her way in (by flinging literal bags of gold at the Merry Men and begging to be robbed) end in failure. So, disguising herself as Martin, the young brother to her own manservant, she parlays her bits of schoolroom sword-fighting experience into the creation of her own outlaw band–a kinder, gentler, nobler outlaw band, one that tries to help the oppressed peasantry whom Prince John is busily taxing and threatening into even greater impoverishment and despair.

Farr’s adaptation also stands out in how central it makes the economic struggles of the peasants, adding as major characters two children whose father refuses to pay John’s taxes and is executed. It highlights the ways in which Robin Hood’s quest–here refigured as Marion’s–is not so much redistributing to the poor wealth that rightly belongs to the rich, but returning to the poor the very sums that have been painfully extorted from them. But when her goals of protecting the peasantry and protecting herself start to conflict, Marion faces some difficult choices.

According to HVSF artistic director Davis McCallum, the company has been interested in this piece for several years, and the season was officially programmed in the fall of 2017, just before the Harvey Weinstein story broke and the #MeToo movement started a national conversation on women’s sexual agency. Agins’s production speaks passionately to the issues raised by that movement; the power dynamics between Marion and Prince John, who literally cannot imagine any outcome other than possessing the woman he desires; his casual assumption of social and sexual dominance over her is chilling, even as this lends more impetus to Marion’s desire to head for the woods–and to disguise herself as a man. As McCallum says, in male disguise, Marion “has access to all the things men have access to—rage, sexuality, confrontation, physical freedom.”

Marion’s centrality as a moral agent and protagonist puts her in a traditionally masculine role (both as Martin and as Marion), but she also serves the more conventionally feminine role of teaching Robin Hood how to access his emotions. Agins sees a great deal of nuance in that characterization, though. She says, “One of the things we’ve been seeing a lot in the past two years is a dearth of empathy. How do you teach empathy? I do think that we tend to posit emotion as feminine, and [Marion] does hold that place in the narrative, [but] I was trying to think of it in a broader sense. She shows up [in the woods] for all the world like a rich girl going to volunteer at a soup kitchen. She is coming from a very specific set of assumptions and there is empathy there, but also tone-deafness.” In other words, while she does end up serving as a sort of emotional catalyst for Robin, Marion, too, has a lot to learn about empathy and about really engaging with the needs and wants of others.

Agins continues, “She learns something about self-sacrifice. It’s easy to throw your money around and find some measure of freedom in that, but the moment she decides that someone else is more important than she is is extraordinary. You could argue that women are called upon to sacrifice in that way more often than men—but she’s not just running around teaching people about feelings; she learns and grows and fails.” She learns, for one thing, to actually be an agent of change, to be, not just someone casually aware of how unfair the world can be, but someone who fights actively to help others. And, in the end, she gets to become someone who lives and loves, the way she prefers–in the woods, married to Robin, and probably having a little duel now and again, just for fun.

Like a Shakespearean comedy, a family-friendly show generally needs an upbeat ending, one that ties up the plot and promises happily-ever-after. After so much focus on a central female character striving for autonomy, the obligatory wedding in the final scene can feel like a little bit of a letdown. But Agins’s production spotlights Marion’s strength till the end: even when she’s about to be forced to marry John, dressed in a glittery wedding gown, she’s damn well going to participate in her own rescue. The minute Robin and the Merry Men reveal themselves, she gets her hands on a sword and continues to fight. The empowering message is not lost on the audience. As Agins says, “A lot of people bring kids, and after the show the kids are playing on the lawn—and to see little girls pick up sticks and begin sword-fighting feels like we’ve really accomplished something.”

Loren Noveck is a writer, editor, dramaturg, and recovering Off-Off-Broadway producer, who was for many years the literary manager of Six Figures Theatre Company. She has written for The Brooklyn Rail, nytheatre.com, and NYTheater now, and currently writes for The Brooklyn Paper and Exeunt magazine. In her non-theatrical life, she works in book publishing.

Hudson Valley Shakespeare Festival runs until September 3, 2018. Look for Summer 2019 Season announcement this November.

Interestiing thoughts